Native bees in the garden

Paul West explains how to bring more native bees into your life and gardens by encouraging their natural habitats.

Blue banded bee photo by Alamy

Bees are a hot topic right now, but did you know that Australia is home to a staggering 1600 plus species of native bees? They range in size from 2–24mm and come in a vast array of colours and shapes. You’ve probably heard of native stingless bees (Tetragonula carbonaria), which are becoming increasingly popular for people to keep in their backyards in warmer regions. They are one of 11 species of native bees that are social and stingless, while most of the other native species are solitary, live in burrows, and are able to sting. If you’re not interested in keeping bees, there’s still plenty that you can do as a gardener to provide food and habitat to lure native bees into your garden and support them in a time of dwindling wild habitats.

Know your bees

Get your hands on a guide book to native bees or head to an online resource like Aussie Bee (aussiebee.com.au) and get to know the species that call your area home. Next, observe the pollinators that hang around flowers in your garden. You can tell bees apart from insects such as flies and wasps by the presence of pollen on the back of their legs or under their abdomens. Some common varieties that you may observe include resin bees, reed bees, masked bees, leaf cutter bees, blue banded bees, teddy bear bees and stingless bees.

Water and food

Bees need access to water, especially in summer. You can make your own bee watering station by filling up a bird bath or an old baking tray with water and adding some rocks so that they stick out above the waterline allowing the bees to land and drink without drowning. Place the watering station in a cool, shady spot near some flowers in your garden where you’ve spotted some native bee activity. Native bees also need access to pollen and nectar. To create the ideal smorgasbord, grow at least four different types of plants flowering at any one time and have a variety of plants flowering continually throughout the year. Arrange plants in your garden in diverse stands, that can be a mixture of both natives and exotics, being sure to include native plants local to your area for maximum benefit. Bee attracting plants include banksia, borage, bottlebrush, lavender, grevillea, salvia, eucalyptus, native peas, native rosemary, tea trees and daisies.

Habitat

Bee house, insect hotel, Halls Gap Botanical Gardens Photo by Denis Crawford

Native bees have diverse habitat requirements, depending on the species. The majority of native bees are solitary and don’t build the wax structures we generally associate with honey bees, instead building small nests or burrows in bare soil, borer holes, plant stems or in small cavities under bark or rocks. To maximise natural habitat, leave some bare ground undisturbed and unmulched around flowering plants, and where it doesn’t pose a hazard, leave plenty of wood, branches, posts and logs. You could also try your hand at making your own native bee “hotel”. A quick search online will provide you with a stack of different designs, with most consisting of a mix of wood, stems, straws, mud and sand. However, it has become clear that too many shapes and sizes together in the one hotel provides shelter for predators and prey, and the predators pretty quickly see off their prey. It’s better to have lots of smaller hotels with nesting spots for only one or two different bees.

Native bees as pollinators

Bees play an important role in pollinating the food crops that we all eat, with 65 per cent of crops grown in Australia requiring some form of bee pollination. If the Varroa mite were to reach our shores, it’s devastating impact on European honey bees would be sorely felt by farmers whose crops rely on bee pollination. Fortunately, native bees appear to be resistant to Varroa mite and researchers at the University of Western Sydney are currently exploring the suitability of various species of native bees to act as pollinators for various food crops. The research also explores whether or not native bees could be used to pollinate greenhouse crops, with a particular focus on blue banded bees and greenhouse tomato crops. The blue banded bees are buzz pollinators and with the absence of wind, greenhouse tomatoes require buzz pollination, a task that is currently done manually. The question the scientists are asking is: can the blue banded bee be introduced to and survive in greenhouses in sufficient numbers to make an impact?

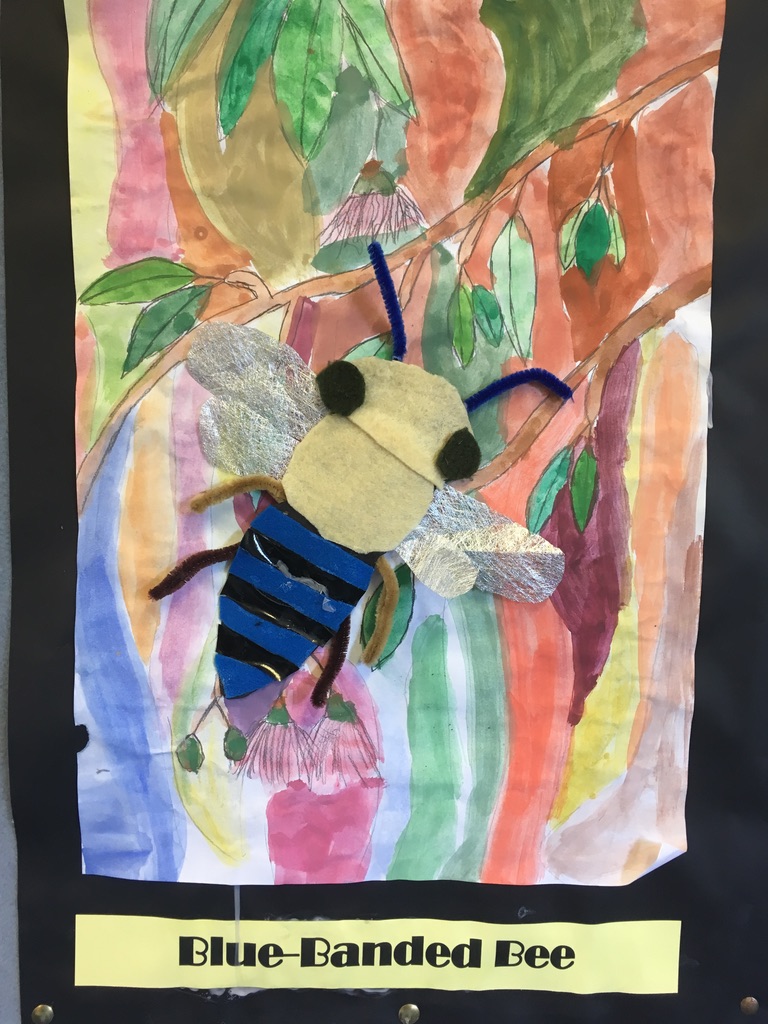

This beautiful artwork of a blue banded bee by Katoomba Public School student, Rose Woodburn, was produced as part of a Year 3/4 Science lesson on pollination.

Teacher Sue Campbell-Neale explains: “In learning about the anatomy of a flower students examined cross-sections of flowers to understand the parts involved in pollination. And in understanding the anatomy of the bee each student looked closely at one native bee.”

Inspired by images from the Native Bees of New South Wales poster by Gina Cranson students created anatomically correct representations of their bee using various materials and painted a native bush background.

Co-op members and Katoomba shoppers will be treated to an exhibition of more native bee art from Katoomba Public School students in the Big Little Gallery art space very soon!

This article first appeared in ABC Organic Gardener magazine and is published with permission. Check out the super subs offer from Organic Gardener in our December newsletter.

SPECIAL SUBSCRIPTION OFFER FROM ORGANIC GARDENER MAGAZINE