Wild about fermentation

Naturopath, Sonya Byron, discusses the many benefits of fermented foods and shares a simple kraut recipe.

Fermented foods are growing in popularity, with more and more people purchasing foods such as kefir, kim chi and kombucha, or making their own at home. These foods are claimed to benefit everything from digestive to immune to mental health, but is there any truth to these claims? Here’s a brief look at fermented foods, what they are, and their many benefits.

What is fermentation?

Fermentation is the chemical process through which the growth and metabolic activities of microorganisms, such as bacteria, yeast and fungi, convert carbohydrates into acids or alcohol. As cabbage is fermenting, for example, lactobacilli bacteria are converting carbohydrates into lactic acid, and tangy and delicious sauerkraut or kim chi is the final result! This may sound high tech, but anthropological evidence suggests that our ancestors have been fermenting foods for 10,000 years.

What are the benefits of fermentation?

1. Preservation

The first and most obvious benefit of fermentation is preservation. Before the days of refrigeration, our ancestors fermented highly perishable foods to extend their shelf life and to ensure a reliable supply of food, especially through the winter months when fresh foods were often limited in availability. A fresh cabbage left sitting on a shelf will rot within days or weeks, that same cabbage converted to kim chi or sauerkraut, however, has a shelf life of months or potentially years.

2. Flavour!

Fermented foods offer an amazing array of tangy and sour flavours and are delicious either enjoyed on their own (think wine and cheese), or added to other foods to enhance their taste. This is why humans add sauerkraut to hot dogs!

3. Digestion

Fermenting foods can make them easier to digest, and this can be especially beneficial for people with certain food intolerances. Many lactose intolerant people can enjoy yoghurt and aged cheeses such as cheddar or stilton, for example, because the lactose in the milk is converted by lactic acid bacteria into easier to digest simple sugars (glucose and galactose) through the fermentation process.

4. Nutrition

Fermentation both increases certain nutrients within foods, such as B group vitamins (1), and decreases anti-nutritive factors (compounds that interfere with the absorption of nutrients). Phytic acid in beans and grains may bind to minerals such as iron and zinc, for example, and the process of fermentation reduces phytic acid, making these minerals more bioavailable (2). This may be another reason why our ancestors fermented some foods before consuming them (soy beans were traditionally consumed in fermented form as tempeh, miso, and soy sauce, for example).

5. Health

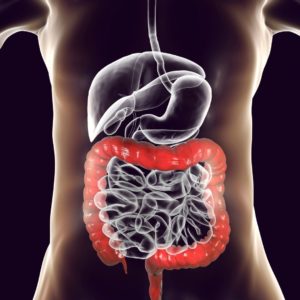

Consuming fermented foods adds a variety of probiotic microorganisms, such as lactobacillus and bifido bacteria to the gut, and research increasingly indicates that this can enhance the overall diversity of the gut microbiota, with resulting benefits for digestive health. Digestive system conditions such as Irritable Bowel Syndrome, and diseases such as Crohn’s disease and Ulcerative Colitis may benefit from the addition of fermented foods to the diet, for example (3). By extension, our immune and nervous systems may also benefit from fermented foods, considering that 70-80% of our immune cells are within in our gut (4), and (amazingly!) up to 95% of our serotonin (an inhibitory neurotransmitter important for mood stability) is produced in the gut as well (5). A happy digestive system is therefore vital to immune system function and good mental health. Other potential beneficial effects of consuming fermented foods include protection against pathogens, reduction of blood cholesterol levels, and inhibition of hypertension, obesity, diabetes, and atherosclerosis (6).

6. Affordability and ease!

Fermented foods can be surprisingly affordable, particularly if you make them yourself using fresh, local foods in season. A cabbage that can be expensive to buy at certain times of the year can be found for a few dollars at other times, and easily converted at home into several jars of gorgeous kim chi or kraut with little more than salt and a few simple kitchen tools.

Do it yourself, really easy, mixed vegetable kraut

There are many different fermented foods available for purchase at the Co-op, including sauerkraut, kim chi, yoghurt, kefir and kombucha. If you’d like to try making your own ferment at home, however, why not give this really easy mixed vegetable kraut a go? While sauerkraut is traditionally made from cabbage, these are not always in season, so a great alternative is to make it with whatever you’ve got! Well, almost. Basically, if it’s a vegetable and you can squeeze it, you can turn it into kraut, so if you want to include firmer vegetables, such as carrots, in your mix, I recommend grating them first. I love to make this kraut using whatever local, seasonal, leftover vegetables I’ve got in the fridge so that nothing goes to waste. Give it a go today!

Ingredients:

Mixed organic vegetables of your choice (I like a combination of crunchier vegetables, such as cabbage and carrot, with softer ones, like Asian greens).

1Tbsp salt per kg of vegetables (Himalayan pink or Murray river salts, both available at the Co-op, are my favourites. I recommend avoiding Celtic sea salt, which tends to produce a mushier kraut due to its moisture content).

Herbs and spices of your choice (think beyond caraway seeds, and add any herb or spice you enjoy to your kraut. I love adding big bunches of fresh basil, coriander or dill to mine).

Method:

Finely slice your vegetables, grating any that are particularly firm. Tare the weight of a bowl, add your vegetables, herbs and spices to obtain their combined weight, and calculate 1 Tbsp of salt per kg of vegetable mixture. If you have 2.5kg of mixture, for example, measure 2.5Tbsp of salt. Add the salt to the mixture, put on some good music or a podcast, give your hands an extra wash, and start mashing and squeezing your vegetables (use your hands, or a tamping tool or rolling pin to help you if you like). When you can pick up and squeeze a handful of the mixture and the juice runs easily, you’re ready to pack your kraut. Scoop your mixture into your fermentation crock (available at the Co-op) or jars, pressing firmly down as you go. When each vessel is filled, add krauting weights, a smooth stone, a folded cabbage leaf with a chunk of carrot, etc. to ensure that the mixture remains below the brine, as this will prevent moulds from forming on the surface. Cover the vessel and allow the veg to ferment for at least 7 days. I like to allow at least 3 weeks, and some people ferment their vegetables for even longer.

NB: If you’re using a crock, the gasses that arise through the fermentation process will be released with no effort on your part, however, if you’re fermenting in jars you’ll need to “burp” them once or twice daily to release these gasses or your vessel may explode!

Sample your kraut after about a week, and weekly thereafter to determine the perfect ferment time for you. Refrigerate when it’s ready, and then add your finished kraut to anything and everything – it’s for more than just hot dogs! I like to enjoy mine as a side to pretty much any dish, and it’s especially good added to scrambled eggs and vegetable soups.

Top tip!

Sodium levels in sauerkraut can be high, so if you would like to reduce the salt in your mixture, experiment with adding a little brine from a previous batch, whey from your yoghurt, celery juice, or even seaweed and see how you go! Be aware that salt draws fluids from your vegetables via osmosis and hardens pectins, so a lower salt ferment will result in less crunch, and will also be more prone to development of surface moulds. Low salt or salt free krauts are often more successful if the ferment time is shorter and they are refrigerated sooner. The Co-op also sells probiotic cultures that can speed your ferment time so you can refrigerate your kraut earlier.

One of the Co-op’s in store practitioners, Sonya Byron, is a naturopath and yoga teacher in clinical practice at Lower Mountains Health & Healing in Blaxland. Prior to her career in natural health, she earned her living as the owner/farmer of Good Karma Farm, a sustainable two-acre organic farm producing 60 different vegetable and herb crops. She believes that fresh, healthy, home grown food is one of the foundations of good health, and she’s passionate about empowering people to care for their health (and to save money, time and the planet in the process) by learning how to grow and preserve their own food, and how to make their own simple herbal and nutritional remedies for common health complaints. For further information, visit Sonya Byron Plant Medicine at sonyabyron.com.au

(The information in this article is for educational purposes only and is not intended as a substitute for health care advice. Please consult your friendly local naturopath, herbalist or other health care practitioner for personalised advice, particularly if you have a diagnosed medical condition or take pharmaceutical medications).

References

1. Denter, J., Bisping, B. (1994). Formation of B-vitamins by bacteria during the soaking process of soybeans for tempe fermentation. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 22(1), 23-31.

2. Liang, J., Han, B., Nout, M., & Hamer, R. (2008). Effects of soaking, germination and fermentation on phytic acid, total and in vitro soluble zinc in brown rice. Food Chemistry, 110(4), 821-828.

3. Santiago-López, L., Hernández-Mendoza, A., Vallejo-Cordoba, B., Wall-Medrano, A., González-Córdova, A. (2021). Th17 immune response in inflammatory bowel disease: Future roles and opportunities for lactic acid bacteria and bioactive compounds released in fermented milk. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 112, 109-117.

4. Wiertsema, SP., van Bergenhenegouwen, J., Garssen, J., Knippels, LMJ. (2021). The Interplay between the Gut Microbiome and the Immune System in the Context of Infectious Diseases throughout Life and the Role of Nutrition in Optimizing Treatment Strategies. Nutrients, 13(3), 886.

5. Kim, D., Camilleri, M. (2000). Serotonin: a mediator of the brain-gut connection.

The American Journal of Gastroenterology, 95(10), 2698-2709.

6. Şanlier, N., Gökcen, B. B., & Sezgin, A. C. (2017). Health benefits of fermented foods. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 1–22.